We finished our last section with A Discussion of Boolean Logic and looked at how it can be used to conditionally execute logic. In today’s discussion we will see how the core Boolean operators can be composed to model arithmetic. To begin, it may be beneficial to look at how our decimal number system works.

In the decimal system, we use digits 0 through 9 as integer increments. On increment by 1, if the current digit is 9 we reset to 0 and increment the next column when the current column increments. Each increment in the tens column is equal to ten increments in the singles column. This defines base-10. Similarly, it is possible to define a number system using any base! Below, we show behavior in Base 2, 4, and 10 for reference.

Looking at the incremental operation in Base-2, there are some characteristics which may be worth noting.

- When the current value is 0, an increment will cause this value to set to 1.

- When the current value is 1, an increment will cause the next power element to increment by 1. This value will set to 0.

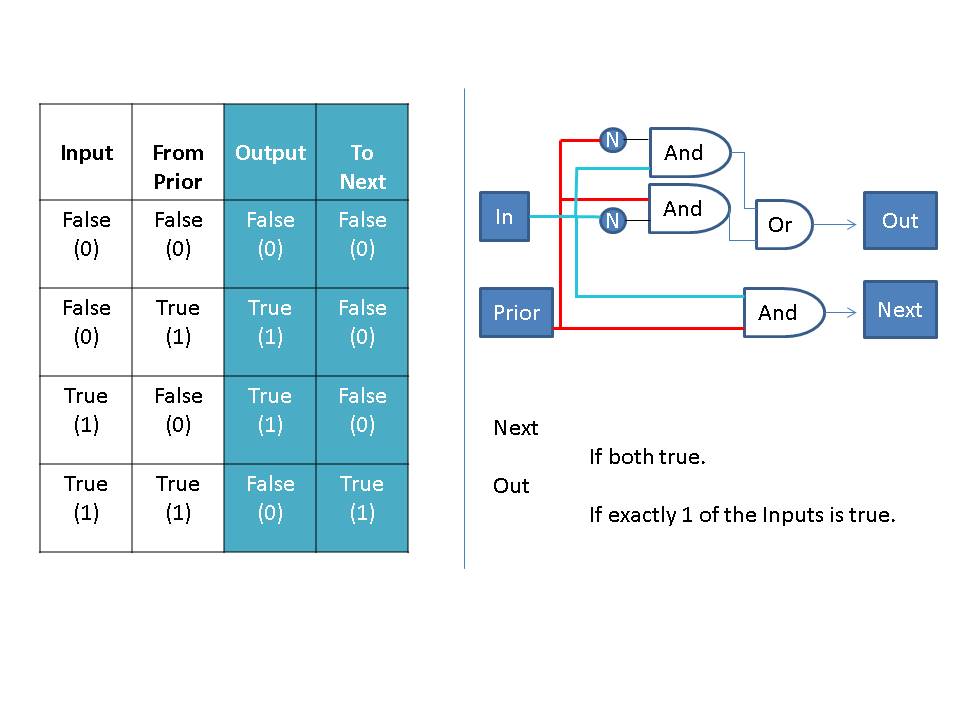

Following this train of thought, For a single bit how can we make sure the above statements are true? The above is known as a half-adder, because it only adds an input and some carried value. The full-adder includes an extra input to support addition of 2 inputs with a carry. By chaining the “To Next” of the current addition to the “From Prior” of the next addition, compounded addition can be performed. For more information on how this chaining is done, see this link on ripple carry adders. At this point we can define a similar setup for subtraction, but that adds limitations and complexity surrounding usage. In particular, there is no support for negative integers.

The above is known as a half-adder, because it only adds an input and some carried value. The full-adder includes an extra input to support addition of 2 inputs with a carry. By chaining the “To Next” of the current addition to the “From Prior” of the next addition, compounded addition can be performed. For more information on how this chaining is done, see this link on ripple carry adders. At this point we can define a similar setup for subtraction, but that adds limitations and complexity surrounding usage. In particular, there is no support for negative integers.

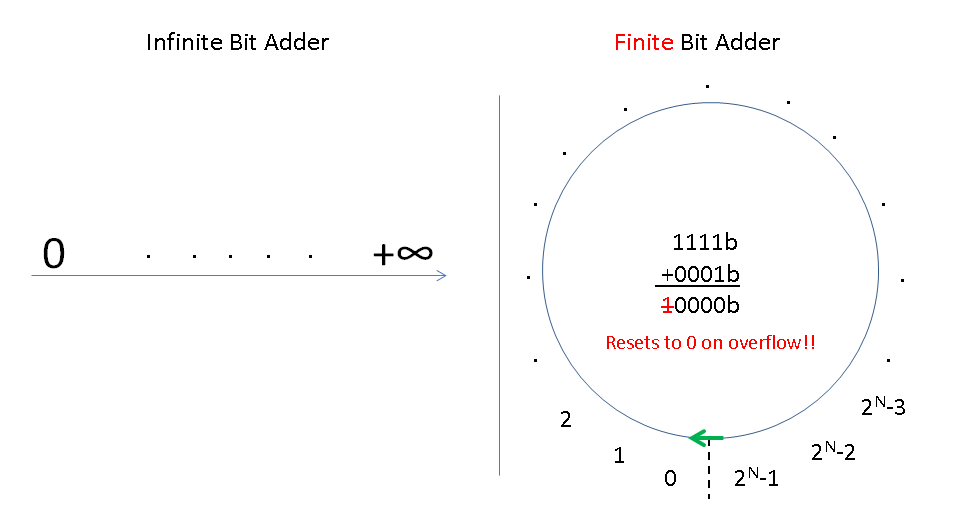

It would be nice if there was some way we could model negative numbers in our current adder. This way addition and subtraction can be treated as the same operation with a flipped sign. One way to do this, takes advantage of the edge case behavior of an adder.

As can be seen in the above diagram, rather than acting as a line the output of a Finite Bit Adder is constrained. Also in the Finite Bit Adder, 1111b negates the 0001b. To generalize, a value N can be negated by counting backward from overflow N steps. This transform is known as 2’s complement form. The transformation can be easily computed as follows:

- Invert all bits of the input number.

- Increment by 1.

In 2’s complement, the number line has been transformed to include negative integers. 2’s complement shifts the number line such that half are negative and half are positive (including zero), which introduces the potential for sign overflow.

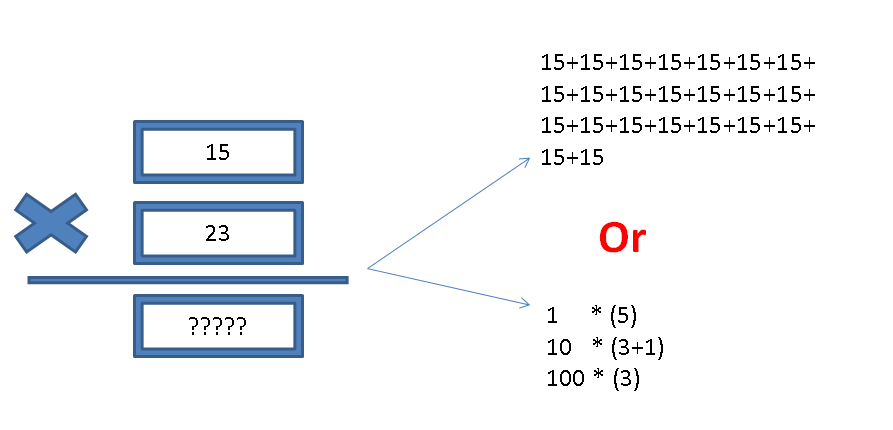

Now that we have a stronger understanding of binary addition and subtraction, formulation of multiplication and division can be treated as natural extensions. By definition, multiplication is repeated addition. However as we will come to see, repeated operations can be a performance drain. Luckily, many of the shorthand multiplication skills we use on pen-and-paper have analogues in binary operations.

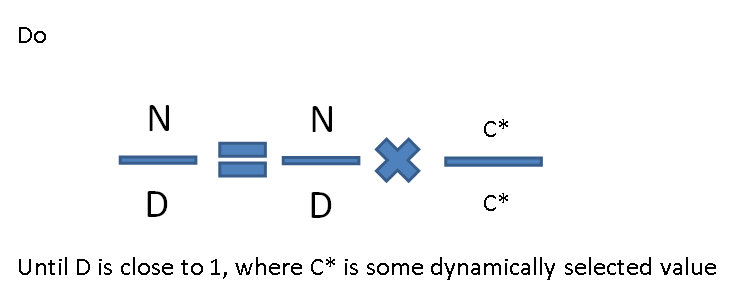

Unfortunately, division lacks solutions as clean as the shorthand above. Many common implementations will convert integers to floating types (see discussion) before processing. One interesting method of floating point division is the Goldschmidt method. The algorithm is as follows:

In this algorithm, as D approaches 1, N approaches the value of the division. Neat!

Discussion:

In this section, we discussed how math can be defined using the logic operations we discussed in earlier sections. We have covered integer math in-depth however in this section, there have only been hints toward non-integer math or floating point arithmetic. In today’s discussion, it may useful to take a brief look at the structure of floating point and implications of usage.

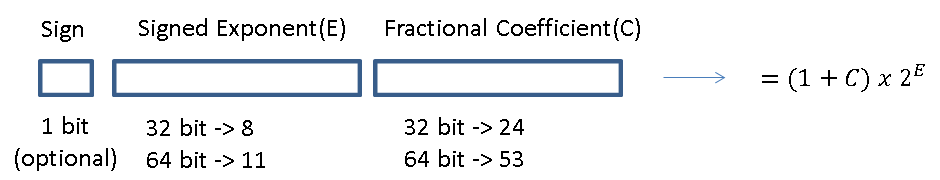

Floating Point values can be considered an umbrella term for different data structures which hold onto numbers as an approximation. Among these the most common format is IEEE 754. This floating point format structures data as follows:

- Sign – When set, the value is negative

- Exponent – Similar to 2’s Complement with an extra offset to support more positive values than negatives

- Fractional Coefficient – Highest precision bit is 0.5, then .25, ……

IEEE 754 values are an implementation of base-2 scientific notation. In order to fit a much wider range of values, some precision was traded away. As a general rule, in situations where exactness is a priority custom data handling may be preferable to float operations. For a more detailed look at the internals of IEEE 754 floating point see this article!